The Beautiful Centre

The Centre is a special place that contains as many mysteries as explanations…but what kind of centers do I mean? Well, the center is in our body-mind unity and extends between the centre of the Earth and infinity. Let us start with ourselves.

We are born with a placenta connected from the centre of our bodies, to our mother. This physical centre remains true for the rest of our lives, yet our mind also has a centre as does our spiritual being. The centre of our consciousness is not necessarily in our heads. Acrobats, gymnasts, martial artists will all give you an explanation derived from their experience. To turn and tumble under complete control, our consciousness needs to be somewhere other than our heads. For the Karate adapt, the Hara is again the navel or the sacral chakra from where the body finds it’s centre. Control of the Hara fixes the practitioner to a single axis or centre of gravity and from this position a balanced and grounded attack can be made, or a defense.

The Dervish in the Sufi tradition spins on the left rotating foot whilst pushing with the other. The experience is to be removed from the visible world or ‘dunya’ and moved vertically on the axis of turning into another realm. The analogy is that the dervishes become like planets as they spin around the Sun, who is the guide, the Sheikh.

Psychologically, the process of becoming adult is similar. As children we tend to run out of control, wobble and fall, like spinning plates left too long. We need adults to check what we do when we edge close to the metaphorical cliff. We are not centred. In maturity we find our balance and with balance a centre. Unlike a pair of scales, the centre is in three or more dimensions, but the analogy works.

If we become too absorbed in a particular activity, such as work or family, or leisure, we neglect other parts of our lives. We indeed neglect our full potential as human beings because the art of being balanced is more important than excelling in one particular area of life. This is contrary to what modern societies tend to expect. We are encouraged to specialise and repeat patterns until we can execute a skill perfectly. This is the process taught to factory workers, concert pianists, teachers, parents or any other career or social position. Time spent on these activities usually is at the cost of other responsibilities. So it is that modern managers will consider the work and life ‘balance’ of employees. It is recognised that becoming a grand master at chess is all very well but creates a lesser human if other simple tasks are not understood, such as working the washing machine or understanding another human’s emotions.

One technique for becoming ‘centered’ is found in both Eastern and Western spiritual practice. The former emphasises the importance of concentration when awake and alert and not becoming distracted by day dreams. Concentration is sometimes taught by training the body before the mind. Students of Zen Buddhism will sit in Za Zen for hours whilst supervised by a master. No movement or involvement in a mental or physical distraction is tolerated. If an earth quake occurred the class should remain motionless. The point is that all that occurs in the world is an illusion that must not be taken seriously, even when catastrophe is imminent. Some deaths cannot be avoided by running, therefore sitting is taking ones noble and inner strength with one into Paradise.

In the West, monks and nuns will sit in contemplation, having already put themselves outside of the world. Although less emphasis is placed on ‘illusion’ the seeker is directed to concentrate on the Divine. The ‘God Head’ is and represents a fixed point, to which the seeker becomes attached in their whole being. By this process all attachment to the outer perceived world falls away as unimportant. The contemplative becomes centred by fixing consciousness to an unmoving presence.

This apparent ‘stillness’ is characteristic of the part of the mystery of the centre. The geographic poles on the spinning earth are not moving at one thousand miles per hour as is the case at the equator. They are the still place which encompasses all directions whilst being themselves directionless.

Throughout time and place humans have found it necessary to identify ‘centers’ outside their bodies.

As the word suggests, the ‘hearth’ in the home is both the centre of the ‘earth’ and the ‘heart’. It generally contains fire as a loyal servant to social well being and survival. It cooks food, warms water and the space around it, giving the householders good reason to gather around.

The village or town containing these homes, will also have a designated ‘centre’. It may deserve that title as a spiritual centre, an administrative centre, a social centre, a business centre, a defensive centre from invaders and other functions.

In ancient times the centre was marked with a significant natural feature such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. So sacred is this ‘centre’ that three major religions revere it ‘s significance as the place where God created the world and the first man ‘Adam’.

In even earlier times societies were sensitive not only to the ‘spirit of the place’ but to a ‘cosmological order’. The ancient Egyptians had a canon of harmonies which Plato referred to in Laws which kept Egyptian society consistently for thousands of years. John Michell refers to this order in his book ‘At the Centre of the World’ p165;

‘The occurrence at different times throughout the world of similarly organised twelve-tribe societies, focused upon a rock, a sanctuary and a sacred king, can only be due to the influence of a common prototype, which must be that traditional code of number and proportion which constitutes the best possible more rational and inclusive image of essential reality’.

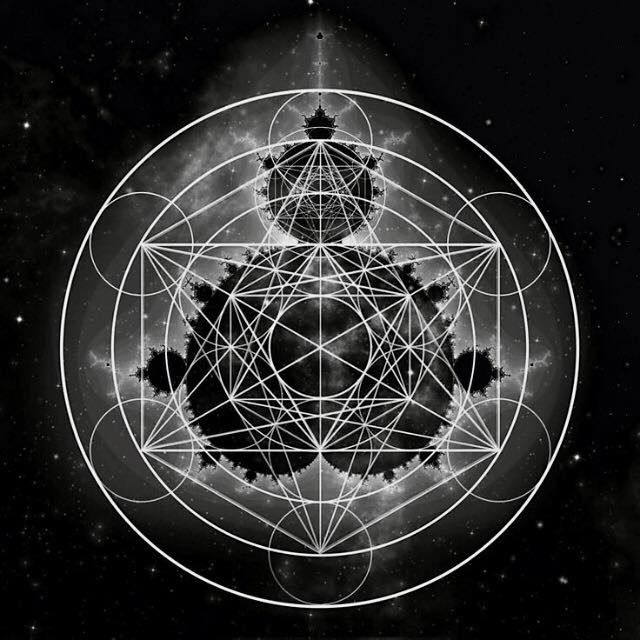

In other words, the centre of the sovereign nation is determined geometrical according to harmonious proportions. Stonehenge in Southern England is a good example of a centre conceived as a circle with twelve divisions. It connects visually with the Universe by alignment with the sun and moon, stars and planets placing the observer / worshiper, firmly at the centre of all things.

The supreme example of a geographic centre is the pyramids on the Giza Plateau which occupy the exact centre of the landmasses of the continents at 30 degrees north.

The geometry of Divine symbolism is a large subject if little understood in the modern world. Towns and cities are conceived for rational reasons of economy and function. If there is a sacred centre to a town it is because it’s ancient forefather conceived it so. In the United States of America the city of Washington is such an example of the application of sacred principles and geometry in city planning, but such examples are rare in the land that built according to ‘the grid’.

In not caring to create sacred centers in our buildings, towns, cities and countries, we are not caring to be ‘centred’ in ourselves. For we are intimately connected with the spaces we occupy whether they are inside buildings, inside the spaces buildings create or within the landscape and cosmos.

As an architectural student in the 1970’s some of my tutors disliked my use of geometry, symmetry and proportion in my designs. Organic shapes were also ‘taboo’. I was told very strongly to design using only right angles and grid patterns, presumably because they had been taught that themselves. They respected only maximising the performance of materials, ignoring the third of Vitruvian principles of architecture which are durability, utility and beauty.

As citizens of the modern world we have learnt only function and forgotten, or care not, to make our buildings and public spaces beautiful.

The change that has to come is for us to enter the centers of ourselves. When we speak from our hearts our social fabric will evolve to transform those places that we hold precious. That is, in my view, the direction for the citizens of the 21st century, but first we must start within ourselves.

‘Go sweep out the chamber of your heart.

Make it ready to be the dwelling place of the Beloved.

When you depart out,

He will enter it.

In you,

void of yourself,

will He display His beauties.

Mahmud Shabistari 14th century Sufi poet