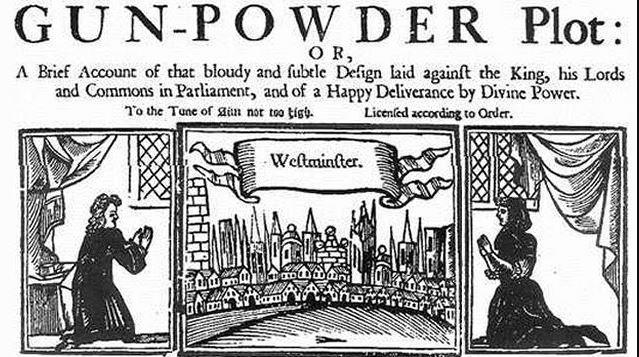

The Gunpowder Plot was possibly conceived and attempted by a group of provincial Catholics in England against King James I. They met secretly to plan an execution of the protestant King by blowing up the House of Lords. The plot was thrawted on the 5th November 1605.

The Cambridge English Disctionary defines a ‘plot’ as;

‘a secret plan made by several people to do something that is wrong, harmful, or not legal‘

We might then define a plot as; ‘a plan with evil intent’. But in the 1960’s a new word was used to define a plot; ‘conspiracy’.

The Cambridge English Dictionary now defines ‘conspiracy’ as;

‘the activity of secretlyplanning with other people to do something bad or illegal: ‘

The difference between a plot and a conspiracy is not clear from these simple definitions.

Please bear with the writer for one final definition as this essay is building up to something which affects us all. What is meant by the term ‘conspiracy theory’ and should we dismiss such theories as ‘conspiracies’?

The Cambridge English Dictionary definition of a theory is;

‘a formal statement of the rules on which a subject of study is based or of ideas that are suggested to explain a fact or e7*-89vent or, more generally, an opinion or explanation: ‘

A conspiracy theory is therefore not a description of truth, although some may take it to be so. It is a ‘suggestion’ which is being applied to explain facts. This may be in a way previously discounted as new facts emerge or are reinterpreted.

Conspiracy theorists are easy prey for derision because of this confusion between a theoretical and and accurate description of an event. Wikipedia describes this well;

‘The term (conspiracy theory) has a negative connotation, implying that the appeal to a conspiracy is based on prejudice or insufficient evidence.’

The notion of a conspiracy theory has itself become the subject of biased logic, when it is derided out of hand without a fair hearing. An example might be it’s use as a term of derision by the United States CIA. They used and perhaps coined it, to discredit disbelievers in the findings of the Warren Commision. This was set up to investigate the assasination of President Robert Kennedy.

The use of the term as an emotional form of ‘mud slinging’ by those convinced to be on the side of rational argument, shows how the accusers can sometimes be as misguided as those they accuse of bias.

When bad things happen, such as a plane crash, there is often ambiguity due to the absence of information from a thorough investigation. Theorists have to match a set of facts with a most likely explanation of what happened.

During the sequential investigation process, various theories will adapt to facts. Eventually investigators will propose a theory that fits the facts more closely than previous theories.

Scientists produce theories which are reviewed by their peers and proven beyond doubt before being adopted as a scientific ‘law’. Einstien’s Special Theory of Relativity is a good example of a theory that could not be proven in his time. Einstien used mathematics to determine the proof of his theories but because the technology of the era was not able to test the theory by experiment, it was long after his death before his theories were proven.

Is it fair that conspiracy theories are given a reputation for being innacurate merely for being supposed to be conspiracy theories. The use of the term as derision is in itself troubling because logically, there is only ever one correct interpretation of events and a so called ‘conspiracy theory’ may be that one. Just as aircrash investigators reach a logical explanation of events so may conspiracy theories, eventually be revealed as true.

The State, or organisation within a State, which attempts to deny events that the theorists are getting right, puts loses trust.

Conspiracy Theories gain considerable credence by focusing on events for which there is no evidence to disprove the theory. For instance, you might suggest that Aliens are already on the planet Earth and have been for a very long time. The subject is so ‘taboo’ in modern societies that governments conspicuously share very little of what they know. Rationalisations are made to ‘explain away’ what witnesses have observed as being something else. For instance a moving light in the sky is explained to be a ‘weather baloon’. If the serving press officer admits on You Tube decades later that this was what he was told to say rather than the truth about a real crashed Alien craft, who are the public to believe?

We live in a time when information is being smoke screened as ‘fake’. We do not know what to believe. It used to be that books and newspapers, that is the written word, were trusted to report the truth. Authors and journalists would lose their reputations and careers if they printed as facts, something which was not from mulitiple, trusted sources. Since the rise of the internet and the general ease of access to all kinds of ‘information’, it is hard to determine between the real, the fake and the absurd.

This phenomenon has been compounded by a growing public distrust in ‘experts’. This is despite the fact that the training and experience of experts means they are right most of the time. After a small amount of research, it is possible to believe you have discovered a truth. What is commonly discovered is that after a large amount of research, you begin to doubt.

Conspiracy theories suffer from this ‘instant expert’ phenomenon and exploit the doubt of reasonably minded people. Complex events, such as the events of 9/11, require observers to be air traffic controllers, communication experts, pilots, air force strategists, architects, engineers, demolition experts, emergency reponse planners and practioners, intelligence officers, politicians, journalists and investigators. There are certainly more areas of experties than these but the point is that investigating the event and it’s motives are highly complex and require meticulously unravelling. Complexity can itself become a smokescreen to baffle the casual observer.

Even simple questions such as, ‘how could two aircraft be used to bring down three buildings?’ are ignored. When there is a pronounced silence from people who should and might know, or worse they start disappearing, citizens should become suspicious.

Fortunately the so called ‘free world’ is open to scrutiny at many levels and Freedom of Information Acts in countries like the USA and UK testify to this. However when clauses are written into these Acts that prevent the release of information publicly for ‘reasons of national security’ there is a window for suspicion to open.

The whole story around ‘Wikileaks’ is a testament to how there will always be room for alternative intepretations of facts or what is termed, ‘my version of the facts’.

If your government derides conspiratorial theories just for being ‘conspiracies’, ask yourself the question, who is hiding what? Perhaps by hiding the truth harm is being caused to citizens of that country? If your government acts in secret and causes harm to it’s populations by an act or ommission or failure to be timely in either or both, is that a plan, plot or a conspiracy?

For instance:why is the Gunpowder Plot so called? Gunpowder is inanimate and does not plot. Surely this was a conspiracy planned by the Spanish Catholic monarchy against the Protestant English monarchy? Or are we not meant to say that?