Common to all the people

The thing with pandemics is that they are far from being ‘unprecedented’ as many politicians offer as an excuse for making mistakes. Historically there is a long list including the plague or ‘Black Death’ as it was known in England.

So aware are public health experts today that, certainly in the UK, pandemics are regarded as the number one risk. Governments have to be prepared for even the most unlikely eventualities and there will be a plan, somewhere. This will describe the risks – particularly the level of harm – and how to mitigate and eventually, eliminate, those risks.

A well thought out emergency plan will include the ‘hardware’ and ‘software’ needed. Warehouses across the country will store vast quantities of ‘just in case’ resources, from dried baby milk to personal protective equipment. Software will be posters and public information announcements already prepared for broadcasting to worried populations. It’s a whole area of expertise and those trained will be employed in all levels of government, from national to local. Protecting the population of a country is, after all, one of the primary functions of government.

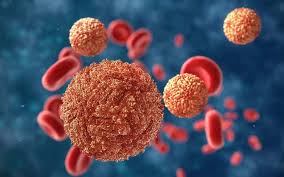

Let us examine, pandemics caused by viruses. To mitigate and plan for a new viral infection there are six stages;

- Identify the origin of the virus and strictly control the contributory factors.

- Analyse the virus and it’s methods of transmission between hosts.

- Analyse the effects of the virus on the human body.

- Identify ways of preventing and treating the virus and it’s transmission.

- Share all of the hardware and software between countries of the World to do the above.

- Initiate prevention and treatment programmes throughout the global population.

At the time of writing there is a pandemic which is estimated as causing between 100,000,000 and 400,000,000 infections a year, according to the World Health Organisation. There has been a dramatic growth of cases in recent decades and at least half of the world’s population are at risk.

The virus causes mild symptoms but in some cases can produce acute flu-like symptoms in humans. There are four serotypes meaning it is possible to be infected four times. According the BBC News App, ‘explosive outbreaks can overwhelm hospitals.’ In it’s most lethal form, fatality rates are 1% of the population when proper treatment and care is available.

Readers will probably have realised by now that I am describing dengue fever or DENV.

It’s a viral infection that you certainly do not want to experience. It’s commonly known as ‘break bone fever’ as it causes severe pain in muscles and bones. Like all viruses it poses a significant threat to the human population.

The good news for those living in high risk urban areas in the tropics, is that a new method of prevention has given very promising results in trial. The BBC News App reports that infections in the city where the trial took place were cut by 77%.

The method used ticks item 4. in my list above. Researchers used a ‘miraculous’ bacteria (Wolcachia) to infect host mosquito’s that spread the virus. The bacteria makes it much harder for the DENV to survive in it’s shared host so the mosquito is less likely to cause an infection. The trial set about introducing this bacteria into the local mosquito’s; fighting fire with fire.

What we can learn, in common with most viral outbreaks is that the origin of the virus and it’s method of transmission must be thoroughly investigated (1. above).

With this understanding, whenever new virus’s are discovered, pandemics can be prevented more quickly and as we know – speedy intervention is vital to reduce transmission. In an ideal world, governments will work together. Knowledge and resources should be immediately sent to the centre of any outbreak and paid for by global contributions rather than the host country, in my view. NGOs and strategic public health organisations, I believe, should be given overall control of treatment of the outbreak, with politicians merely signing off the allocation of national resources. Each country contributes according to it’s means, the rich and those without any outbreaks (pre-pandemic) pay more.

And if one pandemic is given disproportionately more publicity and resources than equally serious concurrent pandemics, what could possibly be the reason? Mind the mind gap!