Words have both sound and meaning and it is these aspects of words that I shall explore in this essay. My case shall be that there is a subtle and hidden level of meaning contained in the abscence of words as well within words; a fact we tend to ignore in our conventional Western tradition.

A child, when it is born, has no words in it’s head. It has not heard human language and it’s world is without word. It is an obvious yet obscure fact that every human infant is capable of learning any spoken language. It listens, and then one miraculous day – ‘da da’ – it speaks.

From that moment on this organic computer learns what we call an ‘operating system’ based on a language; amazingly, any language. This is all very marvellous and yet in the future our language inhibits meaning, rather than expands it.

At a certain stage in life, we might reflect and realise how words dominate our perception. We have become slaves to both the external and internal chatter of ‘things’. Words run away with themselves in our heads and much of the time we might wonder who we are and who is in charge.

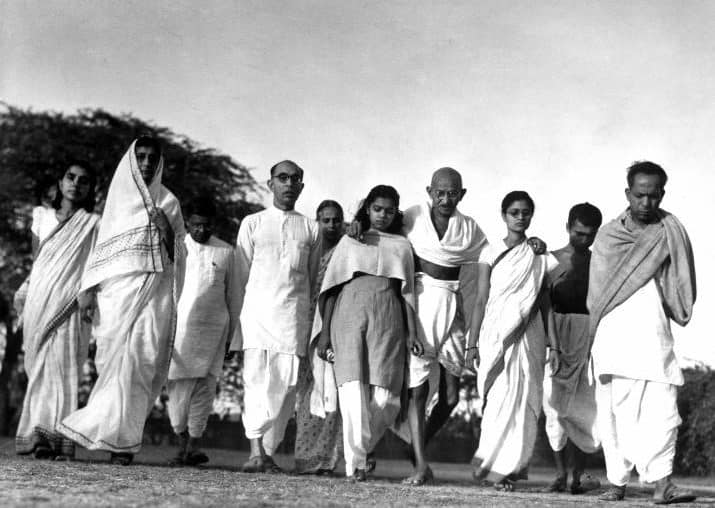

Slavery of the body by another is a very old problem but slavery of the mind is even older. Early philosophers like Socrates, were sent to prison and even forced to commit suicide on account of their desire to cut through the prison bars of language and thought.

Religious and philosophical minds have, at various moments in history, produced a key to unlock the chains that hold us enslaved. In the West, this was done by encoding ritual using a language people did not understand.

In Catholicism this was the Latin language spoken by bilingual priests. Sadly, in recent times church elders have allowed religious incantations to be delivered in the vernacular. The congregation, who previously had been held rather in awe and suspense by the mystery of Mass, suddenly had this balloon popped and replaced by the humdrumness of ‘understanding’. Mystery was unwrapped like presents on Christmas day.

Only those with a deeper calling, such as Christian monks and nuns, are told to move their consciousness away from the meaning of the incantations and ‘just say the words with your mouth’ and ‘keep your consciousness on the presence of God.’ The mystical revelation was that words deceive by reducing mystery to common ‘understanding’. No one explained this to the uninitiated.

In contrast, Islam has not fallen into this trap and in most countries the original words of Divine Revelation are spoken in the original Arabic. Vast swathes of the Qur’an are learnt and recited, without necessarily knowing their meaning, by non-Arabic speakers. When spoken aloud the sound is as important as the meaning as the sounds of the holy words and phrases, even single letters, transmit a power from the Divine.

Exceptionally Mustafa Kemal Ata turk, President of Turkey in the 1920’s and 1930’s, ordered the Quran to be translated into Turkish as part of his ‘modernisation’ political philosophy. Nothing, as they say, is sacred.

Let us pause for a moment and consider the leap of faith that is being suggested here. Behind stories, myths and legends there was always a sacred understanding transmitted from generation to generation. For instance, the mystery of the ‘white stag’ that skips over the horizon or pales into the mist, so evading the hunter, is a mystery that captures and teases with a sense of rapture and bafflement.

This is ‘not knowing’ and has a value that has been largely ignored by ‘rational’ thinkers in the West.

The modern film ‘The Deer Hunter’ 1978 picks up on this theme of and man’s insignificance when compared to the mysteries of Nature. Amidst the heavy hammers of industrialisation, depicted poetically in the opening sequences of a steel works in Western Pennsylvania the central character ‘Mike’ proposes a hunting trip to his friends.

“You know what those are? Those are sun dogs… It means a blessing on the hunter sent by the Great Wolf to his children… It’s an old Indian thing.”

It is hard normally, to sustain this sense of mystery in life, as we reduce it to ‘catch phrases’ and cliché in conversation. We talk to much and our words rattle around other people’s heads like toy trains on a table top track.

Personally, I have always enjoyed travelling in non-English speaking countries and not understanding a word anyone is saying. Instead of grabbing a phrase book to attempt to understand the hubble and bubble of random conversations, I smell the unusual air and absorb the colour of exotic flowers. In essence, the mind can and should be permitted to stand still and pause. There is benefit, if not buying vegetables in a market, from concentrating on the profound reality of consciousness without words; what we might call ‘being aliveness’.

Lewis Carroll, is one of the great nonsense poets in the English language and has guided children and adults into the land of ‘not thinking’ for over a hundred years. ‘Beware the Jabberwocky’ is neither useful nor profound information, without mask or disguise. This sense of the absurd is like a door into the ‘not normal’, a place children love and adults avoid.

It would be wrong to be completely dismissive about words. In poetry and other sublimely expressive forms of language, they can explore and reveal areas of ourselves that are beyond thought, emotions and intuition. Initiation ceremonies into mystery schools are designed to bring about a consciousness that is completely without explanation by language; otherwise books would have replaced all knowledge and experience.

Unfortunately, in the roundabout of real and virtual worlds that we experience today, words come to us in a repetitive form. Anyone who has started to learn a language other than their mother tongue, will understand what it feels like to talk like a child to another adult. We converse like fools and (not wanting to insult the intelligence of animals), like ‘talking animals’.

If we are to search beyond the meaning of words, as far as our human soul will allow, then words perform a function most purely as sound; with or without a perceived meaning. This sound is the most fundamental form of creativity and inevitably appears in multiple opening verses of Genesis in the Bible that begin with, ‘And God said…’. In English these words have meaning but in the original Aramaic their would also be a magical power to the expression, just as magicians incant ‘spells’…Abracadabra! Words have the quality of spells and are learnt by a process dependent on ‘spelling’.

Pure sounds have an effect upon the human energetic system, in a most fundamental way, which is why the music we listen to is so important; as creative energy devoid of meaning. Destructive music such as Heavy Metal, attacks our ethereal essence and can lead to mental and physical illness, should we allow it. The Ancient Chinese respected ‘harmonious’ music for this very reason and viewed the opposite as a signature of decadence in decline in the State.

At the other extreme, music of a spiritual nature elevates our mood and perception in an experiential way. Various mystical traditions around the world, such as Sufism within Islam, embrace these ethereal qualities of music with ecstatic chanting.

There is a tradition in Yoga called Mantra Yoga which uses the repetition of sounds either silently or aloud to stimulate the human subtle energy system known as the ‘chakra’ and at the same time, stop the internal babble of the ordinary mind.

The Universe (of which we are a microcosm) is a cloud of sound as well as electromagnetic energy. Even the planets of our solar system vibrate at a different frequencies to one another and this mysterious concert has been recorded by modern astrophysicists. It is akin to the ‘music’ heard by mystics in trance as a constant hum or combination of harmonious overtones. Pythagoras proposed that the Sun, Moon and planets all emit their own unique hum based on their orbital revolution, and that the quality of life on Earth reflects the tenor of celestial sounds which are imperceptible to the human ear. This truth has often been represented allegorically in Western art as ‘choirs of angels’ playing musical instruments such as the harp and trumpet.

Perhaps the greatest example of the decadence that words can bring is contained in the Biblical story of the building of the Tower of Babel in Genesis. Here the Divine restraint from advancement of civilisation was used to confuse mankind with multiple languages instead of just one. The English language translates the word ‘babble’ as to ‘talk rapidly and continuously in a foolish, excited, or incomprehensible way’. Turn on your television sets today and discover that nothing has changed since this Biblical event! The world spins and makes us giddy, words fail us, we argue and fight, and all fall down.

In the Eastern philosophies, you will find a great emphasis on non-verbal communication. Much of the Japanese tea ceremonies are conducted in silence and participants are taught to ‘know’ how to conduct the ceremony without the interruption of words. A Japanese friend of mine was late for her tea ceremony class and found herself standing outside the room in which the class was taking place. She knew she would be judged on knowing exactly when to open the door and enter the room.

‘Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.’ Lao Tsu