…is ‘paved with good intentions..,’

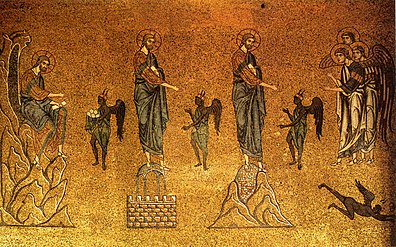

Dualistic thinkers (thinking using opposite terms such as black and white) have a problem with the idea of good and evil. Most spend their lives seeking goodness and avoiding evil. It’s a well intended strategy and one promoted extensively by Christians. Jesus the Christ spent forty days and nights resisting temptation by the ‘prince of the world’…the Devil.

The problem is, life is not so simple as good and bad…would that it were! Would that Western thinkers looked over the shoulders of Eastern philosophers who believe that there is no such thing as pure goodness, nor pure evil. (The corollary is that there is no Heaven and no Hell which is also true but perhaps the subject for another essay.)

In the Yin Yang symbol, which is central to Eastern philosophy, good contains a little touch of evil and evil a nudge of good. Sometimes goodness may just be a thin shell containing a large quantity of evil and visa versa. An example might be the Atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in the second World War. The world would be a better place if that technology had never existed. What you see, is not always what you get.

The past can provide valuable lessons but here I shall use some examples of ‘dualistic thought’ from current Western political debate; there is a tempting assortment to choose from!

The first woe is, ‘Generalisation’. Politicians are by definition, strategists; taking a broad view and delegating attention to detail to minions. They are therefore prone to declare noble ‘aims’ to please voters, such as to ‘reduce inflation, help the vulnerable, create jobs, improve public services’ etc. etc.

What is not presented for examination is how this aim is going to be achieved.

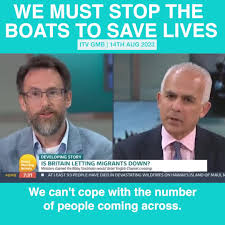

As an example of using the wrong ‘means’, the previous government in the United Kingdom made an election commitment to ‘stop the boats’. This referred to undocumented migrants crossing the English Channel in dangerously unsuitable boats. This aim was presented as ‘good’ because there had been boats sinking and people tragically drowning. The government’s intention was ‘good’; to save life. If the means to stop the boats was challenged, the questioner was accused of wanting people to drown; they were supporting evil over good. The argument was totally dualistic and as a result over simplistic.

The absurdity is that any problem solving plan can be justified as ‘moral’ and ‘benign’ whether it was likely to work or not. It just needs a ‘good’ intention or aim and expects never to be challenged on any other grounds.

The detailed plan to ‘stop the boats’ intended to send failed UK asylum seekers to Rwanda. The plan included breaking international law and expense that did not match the benefit. Worse still it was based on an untested assumption that those willing to risk death by drowning would be put off by a comfortable flight across Africa to free food, health care and accommodation in sunny Rwanda. Asylum seekers from Rwanda would probably not be so pleased as it’s not a safe country by most definitions (but that was a level of complexity too deep to examine). The final cost of this plan was the same as putting up each asylum seeker in the Ritz Hotel in London; an option the Ritz would probably have declined.

My point is that however absurd the detailed plan, the government would repeat it’s justification by asking, ‘do you want people to continue to drown in the English Channel?’ as if that were the only option to achieve their well intentioned aim. Of course it was not the only option but presented as such. In the end the plan was abandoned and hundred of millions of pounds metaphorically thrown into the English Channel at a time when the lack of money in the countrie’s coffers was also a problem.

The new Labour government are now desperately trying to balance the books by not giving pensioners an allowance to heat their homes over the coming winter which they agree is regrettable and may cause death ( i.e. an evil ) but is justified by a need to balance the country’s books (i.e. a goodness )

When politicians are not generalising they present details to prove or disprove a generalisation. A prime example appeared in the news this week during the televised debate between candidates for the forthcoming presidential elections in the U.S. of A.

In this debate between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, Trump purported that migrants were eating the pets of American citizens in Springfield, Ohio. The response of Harris was the only rational one, which was to giggle. Apparently, this story was currently feeding the confirmation bias of social media zealots, which included a person who considers himself fit to rule the world. Fact checkers and local officials confirmed that the story was not true. But this does not stop those repeating it, who wish it was true.

The problem for those caught up in such an argument is that there may have been just one instance of starving migrants cooking up a street animals on a cold and windy night to feed their children. In the world of political debate not using numbers or arguing over whether numbers are true or not, allows generalisations to pass critical examination because even if there is only one instance, the general statement becomes true, even if totally misleading. It’s a gift to politicians.

At the beginning of this essay I referred to eastern philosophy as tending to take a holistic view of events, rather than focus on a particular set of facts. In Surah Al-Khaf in the Holy Quran, Moses meets a figure not named but described as a righteous servant of God possessing great wisdom. Moses watches him damage a humble fisherman’s boat and protests despite being sworn not to question any thing he witnesses. In time, an army passes in need of such boats and ignores the damaged one. The fisherman is able to repair the damage and keeps his boat and his livelihood. There follows other stories where actions are ‘evil’ at first sight, but as circumstances develope, are shown to have been benign.

In conclusion, our world at the present time is full of major choices about which we hear politicians of all persuasions expounding strong views. As humble citizens we have little say in these matters and have to trust those promoting ‘good’ and denouncing the ‘bad’.

Decisions are for reasons suggested above, and in my view, never such a clear cut choice. We assume we make choices based on hard facts, reasonableness and clear routes to known consequences. I contest this assumption and suggest we take a more pragmatic view, summed up in the simple word ‘maybe’.