I am that, I am this, I am

There are three principle perceptions of the human mind. One is not ‘better’ than the other in moral terms, it is just useful to know how one works and experience mental and spiritual states objectively.

The first state of mind is the most common. It is the awareness of something other than self consciousness and is ‘I am that.’ It is the least real of all three and is summed up in the idea of ‘fantasy’. Like all human experience it can be positioned on a calibrated scale from weak to extreme. For example a person watching a narrative such as a film is fantasising, whilst also being aware of their own present mind and body. The fantasy is enjoyable. It fills the potential of unexplored human experience and is fulfilling in the regard of saving time, resources and often personal risk. Imagine watching a film in which the characters visit a wild life reserve in central Africa. There is an experience depicted by characters in the story; one or more of whom, the viewer will identify as being somewhere between ‘likeable’ and ‘I wish that was me’. They might sit in the evening around a camp fire and sing songs with the fire flies scattering in the flames and the crystal stars piercing the ocean black night sky. The roar of a hunting man-eating lion that has attacked several similar parties and is known in the area, sends them rushing to the safety of their vehicles.

This is a typical ‘I am that’ experience. Usually it is benign and is a willing and useful invigorating, promising stimulation to achieve such experiences ‘one time’ for real or just passing the time. It may add the ‘spice’ to an occupation such as those in ‘first responder’ roles experience. But in it’s harmful extreme, it is the illusion that drives a person to commit horrific crimes, such as mass shootings. The fantasy that they have nurtured for possibly most of their lives, finally overtakes their waking personality and they have to act out to achieve satisfaction. Acting out a fantasy is known as ‘psychosis’ and is so common that it is even a defence in law, though not a way of avoiding being withdrawn from society by the State. Humans acting out fantasy for real is not good and needs to be ‘enacted’ within an unreal place such as a modern gamer in ‘virtual reality’. The Ancient Greeks used the word ‘catharsis’ to describe the healing power of mentally exhausting the power of the fantasy over the rational mind, through theatre, songs and stories. Their stories such as Homer’s Odyssey remain powerful descriptions of the rudders, sails and oars of the human mind to this day.

The experience of such fantasy worlds is of course flawed in a very real and obvious way. The objection is ‘this is not you’ or ‘this is not me’ and that is clearly true. If the fantasy of being a world class athlete stimulates a person to become a world class athlete then the fantasy has worked as a transition tool, a stepping stone. But in modern society few get that chance. There is only one winner and one cup, one Oscar, one Nobel Prize. All the rest, in a competitive society, are left with unfulfilled dreams.

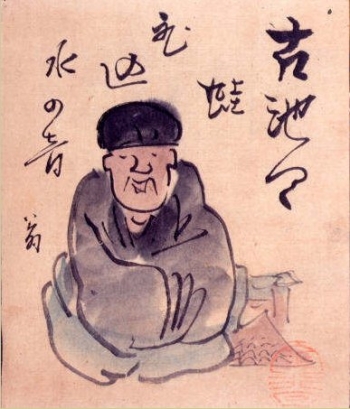

There is another state of mind which overcomes this. It is; ‘I am this’. This is a considerably more profound and rewarding attitude to personal experience. It gives no personal power to ‘the other’ whether these are other people or other activities or other places, times. The simple reward to being ‘I am this’, is realising that mind / personality has no real need to be other than itself. The reward is found in what one truly is. In this state of mind a Zen monk will relinquish identifying with possessions and social status, ‘cleverness’ in intellectual argument and most harmful of all, the allure of the other. Basho, the famous Japanese Zen poet and ascetic, was content with no worldly attachments;

The thief left it behind

The moon at the window

Because mind is realised as a totally personal experience independent of any other thing, the things that mind is not, are described as ‘illusion’ – or the dunna in Sufism, ‘samasara‘ in Hinduism.

The total clarity of ‘I am this’ can be achieved whilst wearing a pin striped suit, or two piece, driving a luxury car and living the a modern life style of ease. It is just that these objects and pleasures are not identified with as being any part of one’s higher self. They are as meaningless as the wind, because the person is continually aware and focused on ‘I am this’. Clearly having wealth and being detached from it, is more difficult than not having wealth and being detached from it. Ascetics have it easy and the Buddha realised this truth after nearly killing his body through starvation. He proposed a ‘middle way’ to truth without physical hardship.

This does not mean believing the fantasy of being a body. The sense of ‘this’ is so fundamental that it excludes one’s own body and body sensations. Buddhists argue quite rationally that if one loses a leg in an accident, one is still complete as a person – therefore we are not our bodies.

The was a song in the 1960’s by Donovan which included the lines;

‘First there is a mountain,

then there is no mountain,

then there is.’

This is a very clear summary of the states of mind being described. The perception of ‘that’ as being real, is seeing the mountain and all it’s mental and emotional associations. These associations are revealed as being mere ‘figments’ of imagination and not real; in which moment the mountain disappears. The relationship between viewer and viewed is realised as just a fantasy.

But of course, the mountain has done nothing through out all of this inner process. It has just done what it has been doing for millions of years – being a mountain.

This is the third state of mind summarised as; ‘I am’. The ‘I am this’ has been dissolved into the mist of the morning by the sun’s rays penetrating the dark night of the soul. The experience of life has become neither object nor subject. Things that were once held as real and true, never were and never will be. The only single experience is to become ‘I’ in the sense that the whole of created things and experience is identical and resonant to what human beings are.

We are not only created in the image of God, we are God and for suggesting this many a Sufi saint and Christian gnostic (Cathars, Templars), was flailed at the stake until death.

The irony was that such holy beings were never in their bodies in the first place and were laughing inwardly, no doubt, all the way to Heaven.